Uber’s Aggregation Woes

What the rise of AVs means for Uber

I’ve been thinking recently about what it is to be Uber in 2024 amidst what appears to be the inevitable emergence of autonomous vehicles from Waymo and Tesla in cities across the United States.

Uber is trading at some attractive multiples, and one reason is that investors have this idea that what’s good for Tesla is ultimately bad for Uber. This assumption is likely quite robust over a 10-year horizon, but I think Wall Street’s excessive focus on the distant future means Uber’s medium-term prospects are currently undervalued.

Prior to examining the long-term challenges faced by Uber from Waymo and Tesla, it is crucial to first understand why Uber is well-positioned to capture substantial value in the short to medium-term.

Company Characteristics:

These are the intangible factors that enable Uber to achieve sustained, differentiated returns.

Brand:

Uber has, by a very wide margin, the most recognisable brand in the ride-hailing industry, but does this allow it to charge a premium? To an extent.

As per Howard Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, a company has brand power when it enjoys higher perceived value on an objectively identical offering, driven by its historical reputation. This allows the business to charge higher prices due to perceived higher quality or reduced uncertainty.

The strongest argument one can make against Uber having brand power is that ridesharing is inherently a highly commodified industry. There is little differentiation between catching an Uber or catching a Lyft, and a substantial chunk of drivers operate across both platforms.

Despite the commodified nature of ride-hailing, Uber retains a degree of brand power—albeit a slight one—simply because it is top of mind for riders. This is particularly true when considering Uber’s global presence. Users can rely on one app whether they are traveling domestically or internationally. Most customers are unlikely to check competing apps once habituated to using Uber, knowing that the platform is reliable and the price difference between competing services is typically marginal.

Uber's limited brand power stems not from differentiated offerings but from its widespread adoption as the default choice for millions. Consequently, Uber derives some strength from its recognisable brand, but it is not their strongest power.

Network Economies:

Uber enjoys some localised network economies. Operating a two-sided marketplace, Uber enjoys a flywheel dynamic with more drivers allowing for greater liquidity in the marketplace and thus cheaper rides for passengers. This encourages additional customers to join the platform, increasing the average price per ride, which attracts more drivers, and so on.

The problem is that these network effects are geographically segmented. A driver joining the Uber platform in Tokyo does not benefit a passenger in Sydney. Uber must therefore invest resources bootstrapping this flywheel in every new market that it enters.

Scale Economies:

This is Uber’s strongest power. Uber is, by far, the largest ride-hailing platform in the world. As a result, they can amortise R&D across a much larger base than their competitors. And there are tonnes of R&D in ride hailing and food delivery, including:

Improving route optimisation to reduce wait times and travel duration for passengers

Developing more accurate GPS tracking for better pickup and drop-off accuracy

Refining driver incentives and support systems to improve retention and reduce service disruption

Adding safety features

Enhancing Uber Eats delivery logistics

Expanding into new markets

These improvements augment the customer experience, and Uber can implement them much more quickly than its competitors. This in turn attracts more users to join its platform.

Switching Costs:

Uber also enjoys moderate switching costs with their Uber One membership program. If a customer is paying $10 per month to get a discount on trips, then they will be less inclined to use a competing platform.

Market Dynamics:

These are the structural challenges within the autonomous vehicle industry that will impede the rapid scaling of Waymo and Tesla.

Rollout Costs:

It is already proving incredibly costly for Waymo to deploy self-driving vehicles, and these costs will only increase as Waymo enters more cities in 2025. Seeking to maximise their return on invested capital, Waymo will initially focus on expanding into dense urban centres. Granted, this is also where Uber makes a substantial volume of its sales, but it still leaves smaller urban centres and suburbs underserved by self-driving cars for a significant period of time. Tesla, in contrast, has a much more compelling scalability proposition, as it already has millions of vehicles on the road that can be converted into self-driving taxis as soon as the software has been developed.

Furthermore, Uber's extensive global presence makes it unlikely that Waymo or Tesla will disrupt its operations internationally in the near future. With services in over 10,500 cities across 70 countries, Uber has established a broad market footprint that would be time-consuming and resource-intensive for Tesla or Waymo to penetrate.

However, this doesn't mean Uber is immune to disruption. The autonomous vehicle landscape is populated with numerous startups, and since transportation is highly localised, a new entrant does not necessarily need to compete against globally recognised brands. Instead, local startups can succeed by offering affordable and reliable services tailored to the specific needs of their region.

Public Scepticism of Autonomous Vehicles

Studies have shown that Waymo, currently the only large-scale operator of autonomous vehicles, is demonstrably safer than human drivers. This conclusion is based on an analysis comparing rates of third-party liability insurance claims between Waymo and human drivers, with adjustments made for mileage and location (arXiv.2309.01206, Waymo Safety Report).

While the dataset remains relatively small, with only 25.3 million miles driven at the end of 2024, the results are promising and expected to improve over time. However, a challenge exists in that public perception often gravitates towards high-profile incidents rather than statistics. Despite Waymo’s comparatively low crash-per-million-miles (CPMM) rate, a few highly publicised accidents could lead to significant public scrutiny. Additionally, as millions of people are employed as drivers for Uber, Lyft, and traditional taxi services, the rollout of autonomous vehicles will inevitably become a politically charged issue, further complicating the public reception of the technology.

Regulatory Hurdles:

This is the market dynamic that is least in Uber’s favour. Self-driving vehicles are already operating in four U.S. cities, and in 2025, both Waymo and Tesla will expand into new markets. While some states may push back as this technology rolls out, regulators are likely to relent under growing public pressure (assuming sentiment doesn’t shift dramatically). Ultimately, it will be hard to justify restrictive regulations when AVs demonstrate public utility, and neighbouring states have already adopted them.

The timeline for overcoming regulatory hurdles is likely to be markedly longer in regions like Europe, which has historically demonstrated much stricter oversight of American tech companies. Furthermore, with big tech companies wielding considerably less lobbying power in Europe and virtually none of the marginal revenue generated per ride benefiting local residents, public pressure to relax regulations may remain limited, at least in the early stages.

Moreover, walking, cycling, and public transport constitute a larger proportion of the transport mix in regions outside of North America. So, improvements in the cost and speed of driving are less critical.

Future Outlook:

So, thanks to Waymo and Tesla, Uber’s future looks increasingly precarious. Self-driving vehicles are not just a strategic complication, they represent an existential threat to Uber, Lyft, and other ride hailing platforms.

One of the fundamental principles of tech strategy, often attributed to Joel Spolsky, is to commodify your complements. Think of Google commoditising the mobile OS with Android to drive demand for its services, or Microsoft licensing Windows widely in the 1980s to commoditise OEMs.

For Uber, the only complement that matters is the drivers—or, looking ahead, autonomous vehicle providers. Unfortunately, it is all but impossible to commodify your complements if there are only two of them.

However, the autonomous vehicle industry is still in its early stages, and this makes it challenging to forecast its long-term trajectory. To better understand Uber's prospects, let’s analyse several potential eventualities:

Solving self-driving takes longer than expected (~25% likelihood):

Self-driving startups have been dropping like flies for the past few years. Uber sold its self-driving car unit in early 2021, Argo AI shutdown in October 2022, followed by TuSimple in late 2023. In February 2024 Apple announced it was scrapping its secretive Apple Car project, and most recently, in December 2024, General Motors announced it would cease funding Cruise.

Evidently, autonomous vehicles aren’t easy. Waymo stands as the only operational robotaxi company in the U.S., and, while Tesla’s story is promising, we are yet to see any fully autonomous Teslas hit the road.

This is without mentioning the significant amount of government regulation and public scepticism that these companies will still need to overcome in the coming years. Remember, Uber was, for years, illegal in many markets it entered.

A final critical factor in the delayed rollout of self-driving cars is the geographic fragmentation of transportation systems. Uber has experienced this firsthand: every new market is essentially a new business, with its own set of regulations, infrastructure, and customer behaviour. This is a far cry from scaling a pure software business.

Winner takes most (~10% likelihood):

Looking forward five years, it’s difficult to imagine another AV company scaling fast enough to compete with Tesla or Waymo. As such, I have limited this analysis to the prospects of these two businesses.

Waymo:

Waymo is currently in a stronger position than Tesla in that they have autonomous vehicles on the road. However, unlike the current ride-hailing industry, I don't believe AVs will be a winner-take-all market. The key distinction is that a marketplace of AVs does not benefit from the same two-sided network effect dynamics that power ride-hailing. Uber’s dominance came from being the first to achieve critical scale in each market. As Uber grew its driver base, more riders were attracted, which in turn incentivised more drivers to join, leading to further growth and market share expansion.

Waymo, however, does not benefit from this flywheel. While rider adoption will grow over time, scaling "drivers" in the AV context requires substantial CapEx and time—far more so than when Uber was expanding aggressively in the mid-2010s. Tesla has an advantage in that they already have millions of vehicles on the road, but even so, it will still have to compete with Waymo as they scale.Tesla:

If Tesla can perfect its software, it’s well-positioned to scale much faster than Waymo. For each new city that Waymo enters, it must establish local infrastructure—maintenance, support, and charging. In contrast, Tesla already has millions of cars on the road. Even if only 10% of Tesla owners opted to rent out their vehicles as robotaxis, Tesla would have hundreds of thousands of cars available from day one in the U.S. This massive fleet would generate immensely valuable data, helping Tesla to identify which cities to prioritise for launching company-owned vehicles to provide greater volume to passengers.

Tesla will eventually face the same challenges as Waymo: setting up local maintenance, charging, and support in each new city. However, Tesla will still be able to scale more quickly and effectively given that they will have nationwide data on supply and demand dynamics from day one. Additionally, Tesla won’t need to have as many company-owned vehicles.

Entering cities and setting up local operations will be a slow process for both Waymo and Tesla, benefitting Uber in the short term. Ultimately, though, the unit economics will decide the long-term outcome.

Dual-player market (~45% likelihood):

The most probable eventuality in the long-term is that Tesla and Waymo will both compete in this space, and over time other players may carve out niches. As it stands, it is difficult to see how any other companies could compete at scale with the technical capabilities and financial resources of Tesla and Waymo.

In a dual-player market, there is still a plausible scenario where Uber emerges as one of the go-to platforms for booking rides. One can imagine it would be advantageous for a rapidly scaling AV company to maximise customer entry points to their service—Uber, with its massive user base, is an obvious channel to leverage.

If Uber did manage to become an aggregator in a dual-player market long-term, they would not be taking a 30% commission on every ride (especially if Waymo and Tesla continue developing their own proprietary booking apps). The vast majority of the value in this ecosystem would accrue to the scarce resource (i.e. the AV operator). This is essentially wholesale transfer pricing power at play.

A dual-player market would undoubtedly be suboptimal for Uber even if they are able to remain an aggregator.

Other (~20% likelihood):

If new entrants were to enter this market, it could benefit Uber by driving the commoditisation of autonomous vehicles, thereby creating room for more of the value to shift to the aggregator. For Uber to capitalise on this, the shift would need to occur within a relatively short window (i.e. less than five years). If new entrants were to emerge after five years, however, the dynamics would favour Waymo or Tesla, as they would have already established their own aggregation platforms by this point.

Waymo could opt to focus on pure margin dollars by licensing their technology to local operators, allowing for more rapid growth. This would allow Waymo to focus on its core strength: the software. This strategy would, however, involve a degree of risk—Waymo would be reliant on third parties to ensure safety and monitoring. Given that customer trust will be the most valuable (and scarce) resource, particularly in the take-off phase, this model may only be viable as the market matures.

Waymo continues its partnership with Uber and focuses exclusively on operating and improving the vehicles and software instead of building out an aggregation platform.

While it's difficult to establish an exact timeframe for many of these potential outcomes, I expect the future of the industry to become much clearer in 2025, as Tesla begins its robotaxi rollout. Based on my back-of-napkin estimates, I believe there is a 20% chance that AVs could be commoditised before the industry matures. This leads to an important question: if self-driving cars were to be commoditised, would Uber necessarily be the go-to aggregation platform?

Uber obviously has considerable experience in operating a liquid marketplace for transport-related services, but Waymo (with Alphabet’s financial backing) would also be in a good position to build this out. Whilst they don’t have as much relevant experience as Uber, Google, at the end of the day, is the aggregator of aggregators.

Between Search, YouTube, Google Flights, and Google Shopping, Alphabet knows how to build functional aggregators that people enjoy using. This is without mentioning Google Maps, which, after Search and YouTube, is Google’s most important and impressive consumer offering. Google has already experimented with allowing users to book rides through Google Maps with Didi, Uber*, and e-scooter operators like Lime and Bird. So, even if AVs were commoditised, Uber would still face steep competition.

*I checked while writing this article and noticed that now only Didi is offered on Google Maps in Australia. Evidently, the MBAs at Uber know a thing or two about aggregation theory.

A Brief Note on Other Ride-Hailing Platforms:

Before diving into what I think is the best lens through which to view Uber’s situation, I thought I should briefly mention other ride-hailing platforms. After all, there are many markets where Uber is not the dominant player.

There is an argument to be made that Ola and Grab are in better strategic positions long-term since they have dominant market shares in India and South-East Asia respectively. These markets will be much more difficult to develop autonomous vehicles for, due to greater congestion, fewer and less-standardised signage, more inconsistent road quality, a higher proportion of two and three-wheel vehicles, and the fact that the vast majority of AV training has thus far occurred in the U.S.

A counterargument to this is that once a company like Waymo or Tesla has a system with seven nines reliability (per vehicle), then this system could be transposed to a completely different geography with minimal fine-tuning. Driving in India or South-East Asia is inherently more complex than driving in Europe or the U.S., but it is hard to make an argument that there is more than one order of magnitude more edge-cases.

However, implementing autonomous vehicles at scale is more than just a technical challenge. There are also significant political and legal hurdles, and one can foresee that there might be considerable resistance to the idea of a large American tech company displacing local jobs.

Uber and Netflix:

Coming back to Uber, I’ve been reflecting on how best to mentally frame their current position. To me, it closely parallels where Netflix stood in the early 2010s.

When Netflix first launched its streaming service in January 2007, it didn’t have its own content library. Instead, it started as an aggregator of third-party content licensed from traditional studios like Disney, Warner Bros, and NBC Universal.

At the time, this was a win-win. Netflix focused on making their beer taste better (that is, growing their customer base without having to invest in creating their own library of tv shows and movies), and the studios got to licence their IP which gave them a reliable revenue stream and also built brand recognition, encouraging viewers to participate in other parts of their ecosystem (e.g. theme parks and merchandise).

In this era, business models on the internet were still being honed, and aggregation theory was not yet well-understood. Not to mention, streaming was not yet a large market and traditional media companies did not have the resources or will to build out their own services.

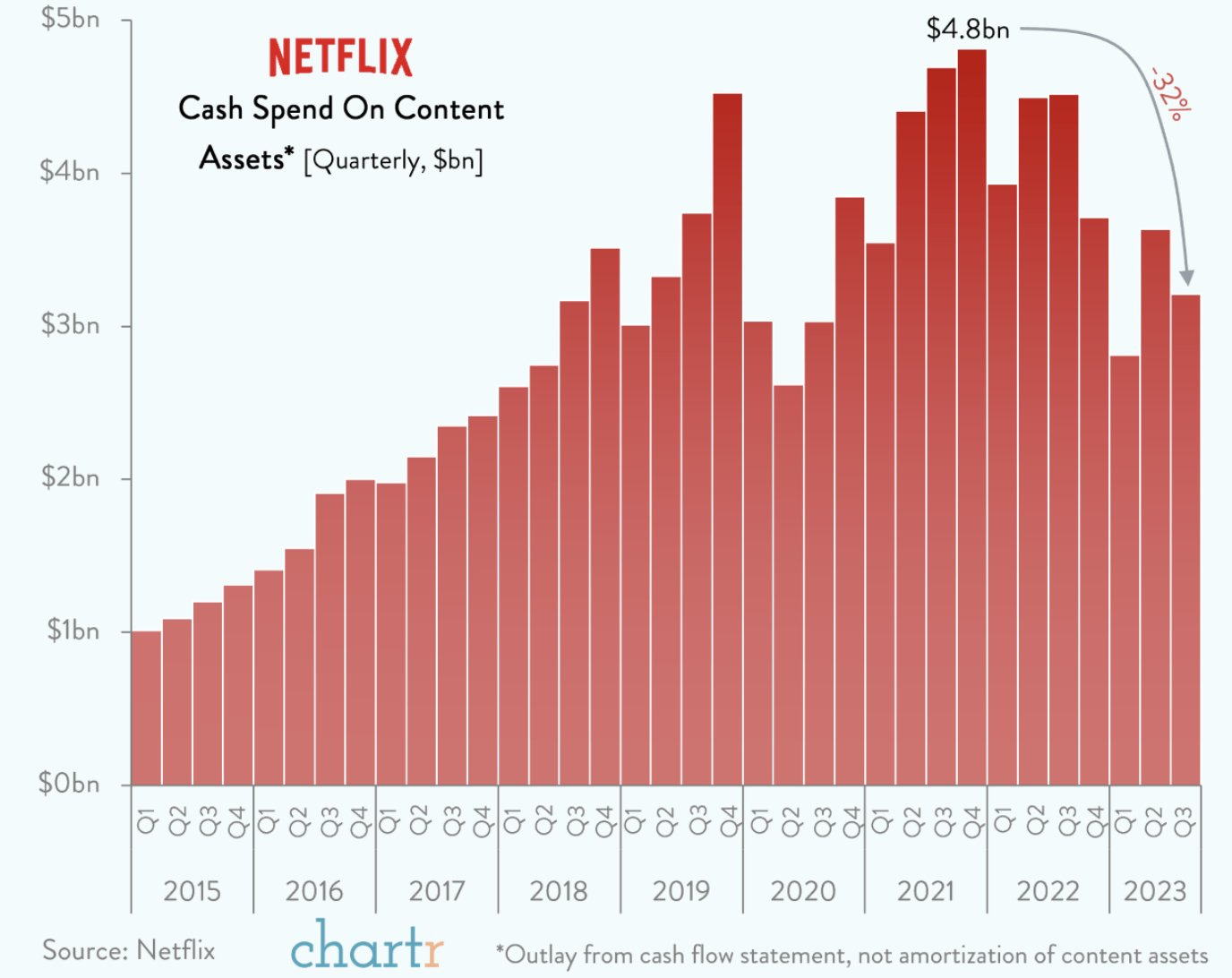

As streaming became a dominant medium through the 2010s, studios invested in creating their own platforms to compete directly at the aggregation level with Netflix. In the late 2010s when traditional studios launched their own streaming platforms, Netflix had foreseen this increased competition and had been investing in their own shows since 2012 and aggressively increasing this spending both in absolute terms and as a proportion of total outlays through to 2019 (see below).

In stark contrast, Uber sold its self-driving car unit, Advanced Technologies Group, at the end of 2020. So Uber has no original shows and can only cross its fingers that autonomous vehicles will be commodified, and that Google or Tesla will not be able to aggregate the demand.

Takeaways:

So that’s the long term. But as I noted at the beginning, Wall Street may be underestimating Uber’s medium-term prospects.

As outlined in the discussion of company characteristics, Uber still benefits from a strong brand, network effects, switching costs, and significant economies of scale. It’s difficult to envision Uber’s relevance in the mobility-as-a-service sector declining meaningfully over the next five years, even as AV operators scale.

A scenario-weighted DCF analysis is out of scope for this article, but this is something I will dive into more in the future. I will be revisiting this every few months as this is a very fast-moving industry and yet is still receiving surprisingly little attention. I suspect this will change as Waymo enters more markets and Tesla starts its robotaxi service in California and Texas later this year.

Overall, Uber has a good chance of navigating this medium-term period, but the long-term calculus looks quite different. In a market that will ultimately be dominated by self-driving, only the best aggregator will survive.

What do you think the key competitiveness of Robotaxi will be in the future? Will aggregator be the key? Or what about the capabilities of autonomous driving technology?

This was interesting Charlie. Having experienced both Waymo and FSD as a passenger, my sense is there is a DISTINCT possibility that success or failure is mostly up to approach. My conclusion on this is perhaps some many paths to autonomy will end as fools errands. Waymo offered their first driverless ride in late 2015. Tesla began offering FSD soon after in 2016. By late 2020 Waymo began offering paid rides to customers! The approaches could not be more different. If the key to learning how to autonomous driving is real miles Tesla should be all the way there as they have 1M+ vehicles using FSD while Waymo has reached a reliable scalable solution with at best 1000 vehicles. That's 1000X more raw data. How could the efforts of such different scales turn out the way they have? My sense of this is Alphabet from the start envisioned this as having NOTHING TO DO with miles driven. Instead they focused from the beginning on creation of a vivid simulation of driving from first principles. Every ride in every city is optimized to evaluate and generate edge cases. I am most interested in Waymo's entry into the Tokyo cab market. The largest taxi market in the free world 2.5X the population of NYC, narrow streets, unrivaled safety environment for pedestrians and right hand drive to boot.

I formerly wrote regularly on Substack and am thinking to return to the platform in the new year. If that is the case, I will consider subscribing to your Substack.